The steel steam trawler Contender was launched form the Aberdeen yard of Hall Russell and Co Ltd., Aberdeen (Yard No 711) on 15th April 1930. She measured 122.4′ x 22.5′ x 12.2′ and her tonnage was 236 gross tons, 101 net tons. She was powered by a triple expansion steam engine by Hall Russell delivering 64 registered horse power.

Originally built for Thomas Devlin and Sons of Granton she was registered there as GN22. She was requisitioned by the Admiralty for service as a minesweeper in 1940, returned to her owners in 1946 and continued to operate out of Granton until the 1960s.

On 12th April 1961 Contender left her berth at Granton for the fishing grounds off Shetland under the command of her usual skipper Donald McKay. They rounded the North Carr lightship and McKay set a course north east by north. This was a trip the Contender and her crew had made many times and perhaps this familiarity was the cause of the stranding of the ship near Cruden Bay some hours later.

The setting of the vessel’s steering when she went aground was still NExE but another trawler, the Summervale, steaming to the rear of the Contender reported that she had taken a very erratic course indicating further lack of attention to the exact course being steered. As they steamed north visibility was poor with a thickening fog. At around 18:20 the Tod Head Lighthouse foghorn was heard off their port bow. By this time they were using their Decca as the only navigational assistance. The danger of using only Decca for navigation was that at times the instrument could ’jump lanes’ if the signal was weak or interrupted and regular checks of position and course using other means was necessary to ensure the safe navigation of the craft. At this time the mate, Duncan Kay, took over the watch from a deckhand named Marshall. Marshall held a valid skipper’s certificate. Kay then gave the wheel to a younger inexperienced deckhand named Monaghan. At this point the skipper of the Summervale was forced to call to the Contender to complain about the erratic course which was in turn endangering his vessel as she gradually caught up with the Contender. This call resulted in the mate retaking the wheel of the Contender.

At this point the skipper returned to the bridge and checked the position and course of the Contender. It appeared that everything was in order at this point despite the erratic course taken to get to their current position. It was now around 20:30 and the deckhand reported hearing the foghorn at Girdleness off the port side. The course was maintained at NExE at full speed and he instructed the mate to keep her outside the 30 fathom contour. He then returned to his cabin. A further watch change took place at 21:45 with another fisherman named Brownlee taking the wheel and steering the same course. Brownlee was not certificated but very experienced having crewed for McKay for more than ten years.

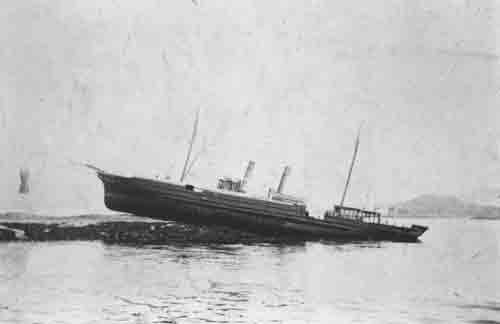

Within minutes of this final change the ship went ashore. The skipper initially thought they had collided with another vessel but, when he rushed to the bridge, found they were ashore. He ordered engines reversed but, hearing the grinding noise of the rocks on the ship’s hull, immediately ordered engines stopped. A radio distress call was sent out and picked up by Stonehaven radio although McKay was unable to give them a precise location. By now the weather was changing with an increasing wind and swell the night cleared and their situation became obvious. An inspection below revealed water entering the fish hold and forward store. McKay ordered the life rafts to be launched. The crew abandoned ship and made it to the shore as the coastguards arrived on the rocks inshore of the wreck. They had run aground on the Veshels Rocks, approximately 2 km south of Whinnyfold in approximate position 57° 22.681’N, 001° 52.716’W.

The Contender became a total wreck. The subsequent enquiry concluded that during the voyage the Decca navigation system had indeed jumped lane and placed the Contender in the wrong position and the wrong course to avoid running aground. They found the loss of the vessel was partially due to the negligence of the skipper whose complacency resulted in a lack of sensible checks on the position and course of his vessel. He was severely censured and ordered to pay the cost of the enquiry. It further held that the loss was primarily due to the actions of the mate who clearly had not taken due care in the navigation of the Contender and the supervision of the crewmen at the wheel during his watch and the absence of the skipper from the bridge. His certificate was suspended for twelve months.